Sixty-eight years ago the director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons paid a visit to a female prisoner in Sing Sing. The prisoner was Ethel Rosenberg, and the purpose of the director’s visit was to convince her to save her own life by giving up information on Russian spy operations and anyone else who might be involved. Ethel flatly refused (as did her husband, Julius). The couple jointly issued a statement avowing that “We solemnly declare, now and forever more, that we will not be coerced, even under pain of death, to bear false witness and to yield up to tyranny our rights as free Americans. Our respect for truth, conscience and human dignity is not for sale.” Less than a month later, Ethel and Julius would die in the electric chair.

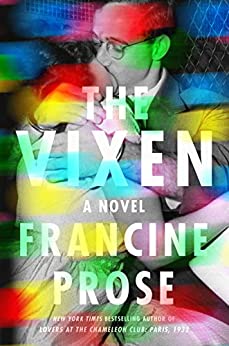

Ethel Rosenberg is not a character in Francine Prose’s The Vixen, but her memory hangs over it like a vigilant ghost. The protagonist, Simon Putnam is a young Jewish man with a faint connection to the Rosenbergs; his mother and Ethel had been schoolmates. After graduating from Harvard, Simon takes a junior editing position at a publishing house that is well-regarded but is also hemorrhaging money. His first big assignment, he learns, will be to edit a more commercial novel than the house usually publishes: The Vixen, the Patriot, and the Fanatic, about a woman who spies for the Russians. The woman — Esther Rosenstein — is clearly modeled after Ethel, while being nothing like her. Where Ethel was a dowdy homebody, a doting mother, Esther is a sexpot with a vicious streak. To edit the novel would be to taint the late Ethel’s reputation — but what choice does Simon have? So he begins the job, hoping to nudge the book into a less tawdry direction. “Keep our memory bright and unsullied” — Ethel’s final admonition to her attorney — rings in his ears like a mantra. And as he works with the author — a mysterious, alluring young woman who lives in a mental asylum — he starts to unwind the secrets behind the novel.

The Vixen is a coming-of-age novel, and for Simon, coming of age means recognizing the layers of artifice that comprise adulthood. At the beginning of the novel, he rues that so much of his life — his very name — seems to conceal who he is. By the end, he is forced to grapple with the idea that everyone lies and conceals. His bosses and coworkers speak from behind façades, and no one is troubled by the idea that an injustice is being done to Ethel, a convicted spy, a Commie. Simon’s Ethel may be more real than Esther Rosenstein, but she is less useful than the titular vixen, who offers a chance to titillate readers while simultaneously educating them on the evils of Communism. In the currency of the Simon’s workplace, truth is far less valuable than perception. The world in which he moves offers no room for nuance.

The Vixen is also a potboiler. You get the idea that Prose had a lot of fun writing the very bad excerpts that she scatters throughout the novel. But her own book — though better written — has as many shocking plot points as the book she is parodying. To be sure, lurid twists are not the point of the book. Prose’s focus is not so much on the twists themselves as on how Simon deals with them. Her real interest is in how Simon’s perspective shifts as he sees those around him in a new light. “Narrative turns on those moments,” writes Simon. “The shock of finding out, the quickened heartbeat when the truth rips the mask off a lie. The friend who is our enemy, the confidant revealed as a spy. The faithless lover, the demon bride. The maniac faking sanity. The deceptively innocent murderer. We enjoy these surprises. We demand them. They delight the child inside us, the child who wants to hear a story that turns in a startling direction. In life, it’s less of a pleasure. There’s none of the bubbly satisfaction of finding out who committed the crime. An opaque curtain drops over the past, obscuring whatever we thought we knew.” Simon spends most of the novel reevaluating what he thought he knew, and then reevaluating his reevaluations.

And yet the realist portrait of Simon sits uneasily inside the frame of a sensationalist novel. Simon is minutely drawn, and I felt that I knew him inside and out — but he is the only character in the book who doesn’t feel like a caricature or an archetype. The villains practically twirl mustaches. Other characters are pushed off-stage as soon as they’ve outlived their usefulness. That’s frustrating, and it also muddles the message of the book. The truth Simon pursues lies in the gray areas, but the people he meets lack any gradations. They are mere rotters, manipulating Simon into acting against his own moral code.

Simon can’t keep the memory of Ethel “bright and unsullied,” of course. That’s not a spoiler; that’s just history. The Rosenbergs may have maintained their innocence up until their executions, but today even their sons acknowledge that Julius probably provided some intelligence to the Russians. Soviet papers made public in recent years reveal that Julius had a codename. So did Ethel’s brother and his wife. Ethel did not. Given the Rosenbergs’ close relationship, though, it beggars credulity she knew nothing about his activities. It’s admirable that the couple refused to give up their friends in the face of death, it’s true that they didn’t give away the atomic bomb, but can they be called entirely innocent? Their story is complicated. And that, perhaps, is the point of The Vixen: truth isn’t a matter of yes or no, true or false; it has subtleties and shadings that cannot be seen in the glare of the everyday world. I only wish more of the characters reflected the complications of reality.